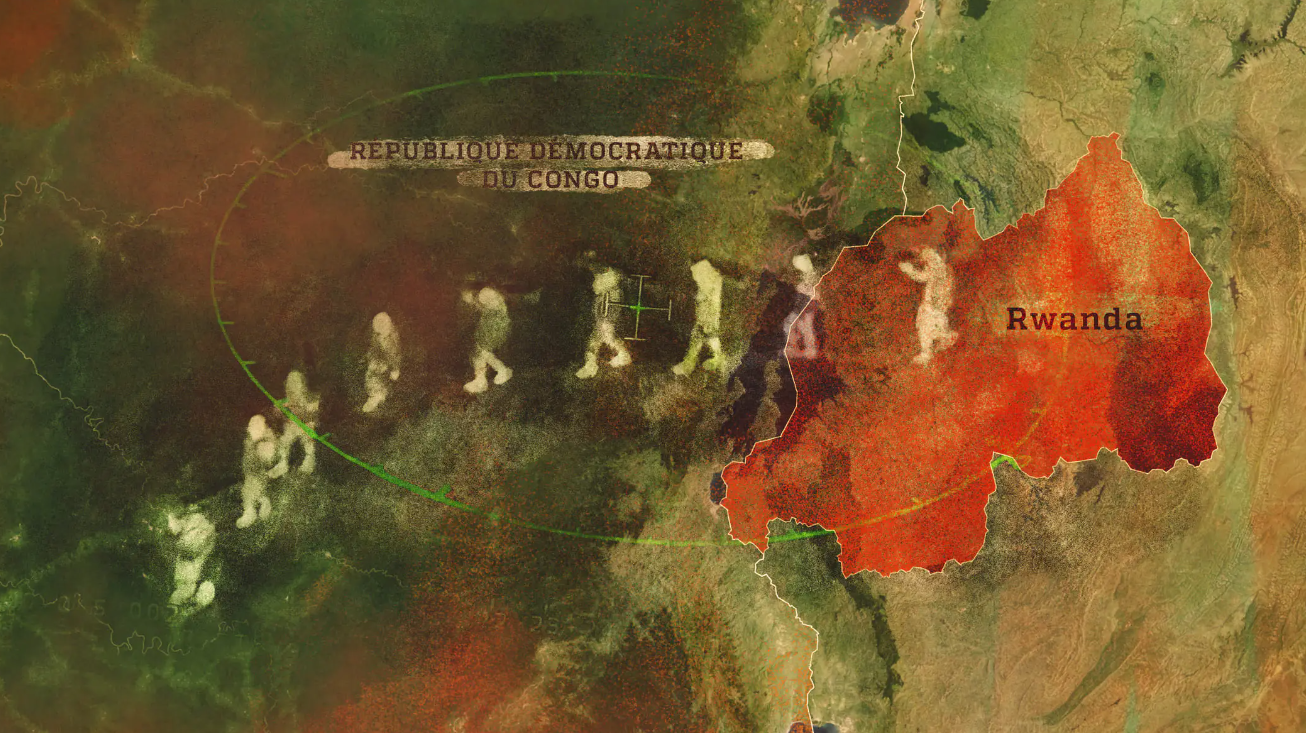

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has published an analysis that has reignited the debate over Rwanda’s role in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Using high-resolution satellite imagery of the Kanombe military cemetery in Kigali, HRW documents a sharp rise in the number of newly dug graves since 2022. The report — which counts more than 1,100 new graves between January 2022 and July 2025, with a pronounced spike during heavy fighting around Goma and Bukavu — raises uncomfortable questions about battlefield losses that Kigali does not acknowledge.

Rwanda’s government has rejected the findings outright. Officials described the investigation as “dishonest,” “disrespectful,” and “obsessive,” accusing HRW of singling out Rwandan graves while overlooking atrocities against civilians in eastern Congo. This clash — satellite evidence versus categorical denials — reveals a deeper problem: competing narratives, limited transparency, and a region where truth is often the first casualty.

HRW’s geospatial study compared multiple satellite images of Kanombe over several years. Their analysis shows a clear acceleration in burial rates:

From 2017 to mid-2021, the cemetery grew at a slow baseline rate. Starting in 2022, the weekly average of new graves increased markedly. The most dramatic rise occurred between December 2024 and April 2025, coinciding with intense M23 operations, when weekly burials peaked.

Altogether, HRW reports roughly 1,171 additional graves in the period under review, with several hundred appearing during the most recent surge of hostilities. If accurate, these numbers point to battlefield casualties far larger than the official figures reported by Rwanda to international bodies.

Rwanda’s foreign ministry and government spokespeople condemned HRW’s work. They framed the investigation as an unfair campaign that exploits the dead and distracts from the suffering of Congolese civilians — including Tutsi communities who have themselves been targeted. Kigali insists it has no troop deployments on DRC soil and denounces any implication to the contrary as politically motivated.

This reaction should be read in context: governments often reject external probes into sensitive security issues. But blanket denunciation without detailed counter-evidence leaves many questions unanswered, especially when independent reports and media investigations point toward the same general pattern.

The HRW findings are not a lone outlier. United Nations reporting, international media investigations, and on-the-ground testimonies have repeatedly alleged Rwandan support for M23 — including claims of troop movement, logistics, and command coordination. Some investigative teams have reported clandestine bases, equipment transfers, and soldiers operating alongside rebel units. These cumulative allegations create a mosaic that is difficult for Kigali’s denials to fully erase.

At the same time, the fog of war complicates exact attribution: some burials may be from training accidents, internal operations, or other causes unrelated to combat in the DRC. Satellite analysis is powerful but has limits; it can count graves and timing, but it cannot, by itself, prove the cause of death or the precise origin of the deceased.

Two facts stand out. First, there is a substantial and unexplained gap between the number of graves identified by independent imagery analysis and the low number of official Rwandan combat deaths reported publicly. Second, multiple independent sources point to elevated Rwandan involvement in eastern Congo, creating a pattern that demands accountability.

Put bluntly: if Rwanda is not recording — or reporting — large numbers of military deaths abroad, one must ask where those buried soldiers came from and under what circumstances they died.

This debate is about more than statistics. It touches on regional stability, international credibility, and the humanitarian cost borne by Congolese civilians. If foreign troops are operating inside the DRC, that raises legal and political issues for Kigali and for the international partners that continue diplomatic, security, or economic ties with Rwanda. If HRW’s work is flawed, however, the organization must be challenged with evidence and method — not only with rhetoric.

The international community’s response is equally consequential. Partnerships and aid, security cooperation, and trade relationships with Rwanda continue even as allegations persist. This tension — between realpolitik and human rights scrutiny — should be central to any discussion of Western engagement in the Great Lakes region.

Is Rwanda’s strong denunciation of HRW convincing, or does it deepen suspicions about undisclosed military activity?

How should the international community balance strategic relationships with Rwanda against credible allegations of cross-border intervention and human rights violations?